The paddy imbroglio: Punjab must introspect

Since the Green Revolution, the minimum support price (MSP) system has been the backbone of foodgrain production in Punjab, Haryana, and western Uttar Pradesh. Despite the predominance of small farms, this system has provided stability, helping India overcome its dependence on PL-480 grain imports in the 1960s and addressing longstanding food scarcity. For over five decades, Punjab has contributed significantly to India’s foodgrain pool, with annual procurements of about 16-17 million tonnes of wheat and 12-13 million tonnes of paddy. Recently, this contribution has averaged 35-40%, depending on production.

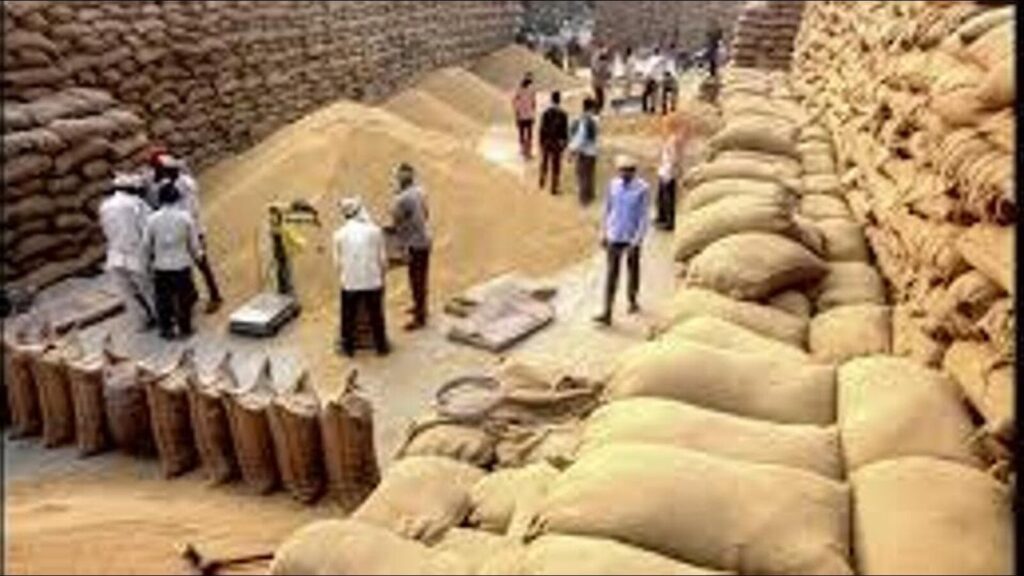

However, this year’s kharif season has exposed substantial challenges. Markets are flooded with approximately 12.5 million tonnes of paddy, but procurement delays have occurred due to slow purchases and logistical bottlenecks. Clearing procured grains from mandis (markets) is hampered by insufficient warehousing and transportation. As a result, farmers are stranded, awaiting payments and fearing delays in wheat sowing for the Rabi season. Concerns over fertiliser access, particularly Di-Ammonium Phosphate (DAP), are adding to farmers’ anxieties. This crisis reflects broader economic strains spilling into the agrarian sector.

Historically, Punjab’s food procurement has been a coordinated operation involving the Union government, state authorities, millers, arhtiyas (middlemen), laborers, and farmers. Even during the COVID-19 pandemic, Punjab managed one of Asia’s largest procurement operations efficiently. So, what went wrong this year?

Logistical blues & poor coordination

The issues this season stem from logistical setbacks, including delays in milling, inadequate storage due to carryover stocks, and unsettled accounts from previous seasons. Fiscal irregularities and a financial gap dating back to 2017 have also been noted with Punjab bearing additional burden of term loans totaling ₹31,000 crore. These strains are still impacting procurement management.

Some political narratives suggest the delays are a punitive strategy against farmers, but this interpretation may be oversimplified. More likely, poor logistical planning and inadequate engagement from both the Punjab and Union governments are to blame. The usual coordination required to ensure smooth procurement has faltered.

The Punjab government, responsible for crafting and implementing procurement policies, appears to have lacked proactive efforts this year. The unrest signals a gap in policy execution. Meanwhile, the Centre, entrusted with national food security and the livelihoods of millions, must also take responsibility for this breakdown. While discussions with millers and intermediaries on profit margins have occurred, tangible solutions are still missing. Greater government intervention is essential to avert farmers’ economic losses and to safeguard national food security.

The immediate priority is to resolve procurement delays. Both Punjab and Union governments must act swiftly to improve warehousing, transportation, and clear backlogs. Timely payments to farmers and arhtiyas are crucial to alleviate financial pressures. Coordination with millers must also improve to ensure timely rice milling; further delays could compromise wheat sowing for the rabi season, threatening food security.

Immediate relief is also needed for farmers affected by DAP shortages. Government intervention here can help address one of the most pressing challenges for the upcoming season, allowing farmers to meet input requirements for the rabi crop.

Overdependence on paddy a problem

Beyond this crisis, Punjab must reconsider its heavy reliance on paddy cultivation, a water-intensive and environmentally unsustainable practice. Punjab’s water table is depleting at an alarming rate of 1.4 feet annually, with some districts facing unsustainable levels. Crop diversification is essential to reduce overdependence on paddy, which consumes about 80% of the state’s water resources.

Punjab could adopt alternative, less water-intensive crops suited to its agro-climatic conditions. Research shows that even a 10% reduction in paddy acreage could save up to 1.4 million liters of water per hectare annually. Haryana has successfully incentivised pulses and oilseeds, and Punjab could implement similar programs, offering MSP adjustments and subsidies for crop rotation. Better financial incentives and market linkages for alternative crops would also help farmers transition to sustainable practices.

Strong political will at both state and national levels is required for such reforms to take hold. The current procurement crisis should catalyse broader agricultural reform in Punjab. With over a million cultivators, 1.8 million landowners, and 1.5 million workers dependent on agriculture, the livelihoods of a significant portion of Punjab’s population are at stake. Punjab and Centre must prioritise economic stability in Punjab’s agrarian sector, crucial not only for the state’s economy but also for India’s food security.

In addition, governance reforms are necessary to prevent future breakdowns. Greater transparency, financial management, and modernization of procurement infrastructure should be central to policy discussions.

This crisis in Punjab’s paddy procurement is a wake-up call. Immediate action is needed to resolve procurement bottlenecks, ensure timely payments, and safeguard crop sowing. Yet, this challenge also presents an opportunity to rethink Punjab’s agricultural policies for a more sustainable, diversified future. A long-term strategy to reduce dependency on water-intensive crops like paddy will ensure a resilient agricultural future for Punjab.

sureshkumarnangia@gmail.com

The writer is a retired Punjab IAS officer. Views expressed are personal.